Binary

Introduction

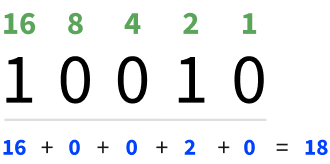

The binary system is a method of representing numbers using only two symbols: 0 and 1. Unlike the decimal system, which uses ten digits (0–9) to represent numbers, binary uses only these two states. Binary is a base-2 system, meaning each digit, or “bit,” represents a power of 2.

For example, binary 10010 equals decimal 18 because $1 \cdot 2^4 + 0 \cdot 2^3 + 0 \cdot 2^2 + 1 \cdot 2^1 + 0 \cdot 2^0 = 18$.

Converting Binary to Decimal

As demonstrated above, the process for converting from binary to decimal is a matter of adding powers of two. For starters, consider this seemingly trivial statement:

\[314 = 3 \cdot 100 + 1 \cdot 10 + 4 \cdot 1 = 3 \cdot 10^2 + 1 \cdot 10^1 + 4 \cdot 10^0\]This 314 is in base 10, so we interpret it as 3 hundreds, 1 ten, and 4 ones. Binary is a base 2 system, so a similar process converts binary numbers into decimal. If each power of 2 in a binary number is given by $b_i$ and the binary number is $N$ digits long, then conversion to decimal follows this formula:

\[d = \sum_{i=1}^{N} b_i 2^{N-i}\]Example: Binary to Decimal Conversion

Question

What is the decimal equivalent of the binary number 100111010?

Solution

Following the formula above, we can write the binary number in a table:

| $i$ | $2^{N-i}$ | $b_i$ |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 256 | 1 |

| 2 | 128 | 0 |

| 3 | 64 | 0 |

| 4 | 32 | 1 |

| 5 | 16 | 1 |

| 6 | 8 | 1 |

| 7 | 4 | 0 |

| 8 | 2 | 1 |

| 9 | 1 | 0 |

The decimal equivalent is therefore:

\[d = 256 + 32 + 16 + 8 + 2 = 314\]Converting Decimal to Binary

While converting from binary to decimal requires a single calculation, converting decimal to binary is a more involved process. Follow these steps to convert to binary:

- Find the largest power of 2 less than or equal to the integer

- Subtract that power of 2 from the integer

- Put a 1 in that power of 2’s place

- If the remainder is greater than 0, return to Step 1 with the remainder

Example: Binary to Decimal Conversion

Question

Convert the number 87 to binary.

Solution

Following the steps above, the highest power of 2 less than 87 is 64. Subtracting 64 from 87 yields a remainder of 23. The next highest power of 2 is 16, so subtract that from 23 yields a remainder of 7. The next highest power of 2 is 4, so subtracting that from 7 yields a remainder of 3. The next highest power of 2 is 2, so subtracting that from 3 yields a remainder of 1. The next highest power of 2 is 1, so subtracting that from 1 yields a remainder of 0. Putting all this together yields 1010111. Note that the zeros here are put in powers of 2 that do not appear in the remainder-finding process. To make this clearer, here is a table with the conversion of 87 to binary.

| $i$ | $2^{N-i}$ | $b_i$ |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 64 | 1 |

| 2 | 32 | 0 |

| 3 | 16 | 1 |

| 4 | 8 | 0 |

| 5 | 4 | 1 |

| 6 | 2 | 1 |

| 7 | 1 | 1 |

Signed Integers

The integers discussed so far have been positive in sign, but negative integers can be expressed in much the same way. Most modern encoding schemes use the two’s complement method to handle negative integers. The steps of the method are:

- Starting with the unsigned integer, flip all the zeros to ones and the ones to zeros

- Add 1 to this value.

To convert a binary number to a signed integer, follow the steps in reverse. First subtract 1 from the number, then

Example: Negative Integer in Binary

Question

Convert the number -9 to binary. If this were misinterpreted as an unsigned integer, what would the decimal value be?

Solution

Following the steps above, we start with the unsigned integer 9. In binary, this would be represented as 1001, with a one in the 8s place and in the 1s place. Flipping the ones and zeros yields 0110. Adding one to that gives a final answer of 0111.

If this was misinterpreted as an unsigned integer, the decimal value would be 4+2+1=7.

Floating Point Numbers

In engineering it is far more common to work with non-integer numbers than with integers. For example, the acceleration due to gravity is 9.807 m/s². In the context of computer programming, these are called floating point numbers, or floats. These numbers can be represented in binary starting with scientific notation in base 2. Taking gravity as an example again, the base 2 logarithm is 3.2938, so it can be expressed as $2^{0.2938}\times 2^3=1.2258\times 2^3$.

\[9.807 = 1.2258 \times 2^3\]A feature of scientific notation in base 2 is that the number on the left, the mantissa, will always be 1 followed by a fraction. This fraction can be approximated using the negative powers of 2. Continuing with the gravity example, the fraction 0.2258 is approximately 1/8+1/16+1/32+1/256=0.2227. We can include the other powers of two by rewriting this as:

\[0.2258 \approx \frac{0}{2} + \frac{0}{4} + \frac{1}{8} + \frac{1}{16} + \frac{1}{32} + \frac{0}{64} + \frac{0}{128} + \frac{1}{256} = 0.2227\]Pulling all the numbers from the top of the fractions gives us the binary number 00111001. That takes care of the mantissa, with the final task being the exponent 3. Since this is an integer, we convert it to binary using the rules for integers. In this case, 3 becomes 11 in binary.

Modern computers commonly use 32 bits, equal to 4 bytes, to contain a floating point number. This is known as a single precision float or single for short. There are also half precision floats, double precision, quadruple precision, and so on - each using varying numbers of bytes to store floats. The single precision float allocates those 32 bits in the following manner:

- 1 bit for the sign

- 8 bits for the exponent

- 23 bits for the mantissa

Image credit: Codekaizen.

This definition was published by the Institute for Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) in IEEE-754. Multiple floating point standards exist due to the variety of applications. Working on a desktop computer with a small amount of numbers would lend itself to very high precision floats. If the data is being transmitted from a satellite, for example, it may be more valuable to send lower precision floats at a faster rate.

While integers can be exactly represented in binary, nearly all floating point numbers are approximations. Modern computers use enough bits to make the approximation error vanishingly small, but cannot eliminate it entirely.

One final note is that rational numbers are not commonly supported. Dividing one integer by another produces a floating point number.

Example: One byte of pi

Question

Convert the constant $\pi$ to an 8-bit floating point. The bits are as follows:

- One bit for the sign

- Four bits for the exponent

- Three bits for the mantissa

What is the exact value of the stored variable? What percent error is there between the stored value and the exact value?

Solution

To convert this value to an 8-bit float, first start by converting it to base-2 scientific notation.

\[\pi = 2^{1.6514\dots} = 1.5707\dots \times 2^1\]This number is positive, so the sign bit is 0. The exponent 1 is the same in binary. Using leading zeros to pad it to 4 bits gives 0001.

The fractional part of the mantissa can be approximated by:

\[0.5707\dots \approx \frac{1}{2} + \frac{0}{4} + \frac{1}{8} = 0.625\]Putting the components together, the full 8-bit representation of $\pi$ is 00001101. The exact value stored in this float is 1.625x2¹ = 3.25. The percent error between the stored value and exact value of $\pi$ is 3.5%.

Why Binary in Computers?

Computers use binary because they operate on electrical signals, which have two distinct states: on and off. Either current is flowing or it is not. These states can easily be represented as 1 (on) and 0 (off) in binary. This simplicity allows for reliable data representation and processing within electronic circuits.

How Computers Use Binary

-

Data Representation: Every piece of data in a computer — whether it’s text, images, audio, or video—is ultimately stored as binary numbers. For example, a single character, such as ‘A’, is represented by a binary code using standards such as ASCII.

‘A’ in ASCII is 01000001.

The table below shows the decimal and binary representations for all capital letters in ASCII.Letter Decimal Binary A 65 01000001 B 66 01000010 C 67 01000011 D 68 01000100 E 69 01000101 F 70 01000110 G 71 01000111 H 72 01001000 I 73 01001001 J 74 01001010 K 75 01001011 L 76 01001100 M 77 01001101 N 78 01001110 O 79 01001111 P 80 01010000 Q 81 01010001 R 82 01010010 S 83 01010011 T 84 01010100 U 85 01010101 V 86 01010110 W 87 01010111 X 88 01011000 Y 89 01011001 Z 90 01011010 -

Logic and Operations: Binary is the foundation of logic gates, which are the building blocks of a computer’s processor. Logic gates perform operations like AND, OR, and NOT using binary input.

- The AND gate outputs 1 only if both inputs are 1.

- The OR gate outputs 1 if at least one input is 1.

- The NOT gate outputs 1 if the input is 0.

-

Storage: Binary is also used in computer memory. A bit is the smallest unit of data, and groups of 8 bits form a byte, which is the standard unit for storing information. The letters in the above ASCII table all use 8 bits. Therefore, each letter is a single byte. Similarly, integers can be stored in several common multiples of 8 bits. Using 32 and 64 bits are common, however this is entirely dependent on the use case. For example, a quadrotor drone has 4 rotors, so only 2 bits are necessary to identify a rotor.

-

Arithmetic Operations: Computers perform calculations in binary. For example, adding two binary numbers like 101 and 011 follows the same rules as decimal addition, with carryovers:

101 + 011 ----- 1000

The Importance of Binary

The binary system is fundamental to the operation of modern mechanical and aerospace engineering systems. From controlling the precise movements of robotic arms in manufacturing to managing the complex navigation systems of spacecraft, binary enables reliable communication between software and hardware. For example, binary data streams are critical in processing sensor readings and executing control algorithms in real-time, ensuring that engines operate efficiently or that an aircraft adjusts its flight path accurately. By understanding binary, engineers gain insight into how digital signals translate into physical actions, forming the foundation for innovation in these advanced fields.